This article is part of a series made available under the Creative Commons Attribution-ShareAlike License by Wikipedia.com

Economic Background Information – Transportation in Ireland

Electrical & Energy Networks – Demographics

Economic Background Information

Ireland was largely passed over by the industrial revolution. One reason given why Ireland did not experience an industrial revolution is because of the scarcity of coal and iron, resources that facilitate an industrial revolution.

However, there were other countries that lacked these resources, but nonetheless industrialised, so there may be other reasons why Ireland did not industrialise.Nineteenth century explanations for why Ireland did not industrialise did not blame the absence of natural resources but that, “The fault is not in the country, but in ourselves; the absence of successful enterprise is owing to the fact, that we do not know how to succeed … we want special industrial knowledge.”

Some historians today point to the sudden union with the structurally superior economy of England. They point out that iron and coal prices in Ireland were as cheap as they were in parts of England outside of the mining centres – and a little cheaper in some parts – and that, on the eve of union with Great Britain, Ireland was industrialising (particularly the linen industry). It may be that, by merging the two economies suddenly, Ireland did not industrialise, but “instead became a supplier of food – and capital – to the ‘mainland’.”

Mass emigration followed in the wake of the Great Famine in the mid-19th century and continued until the 1980s. However, the Irish economic experience reversed dramatically during the course of the 1990s, which saw the beginning of unprecedented economic growth in the Republic of Ireland, in a phenomenon known as the “Celtic Tiger”, and peace being restored in Northern Ireland.

In 2005, the Republic of Ireland was ranked the best place to live in the world, according to a “quality of life” assessment by The Economist magazine. The Republic of Ireland joined the euro in 1999, while Northern Ireland remained with the pound sterling. Both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland entered recession in 2008 and, in 2009, the unemployment rate for the Republic of Ireland was 12.5% due to the 2008–2010 Irish financial crisis.

Back to Top

Transportation in Ireland

Ireland has five main international airports: Dublin Airport, Belfast International Airport (Aldergrove), Cork Airport, Shannon Airport and Ireland West Airport (Knock). Dublin Airport is the busiest of these, carrying over 22 million passengers per year and a new terminal and runway are under construction. All provide services to Britain and continental Europe, while Belfast International, Dublin and Shannon also offer transatlantic services. For several decades, Shannon was an important refuelling point for transatlantic routes. In recent years it has opened a pre-screening service allowing passengers to pass through US immigration services before departing from Ireland. There are also several smaller regional airports: George Best Belfast City Airport, City of Derry Airport, Galway Airport, Kerry Airport (Farranfore), Sligo Airport (Strandhill), Waterford Airport and Donegal Airport (Carrickfinn). Scheduled services from these regional points are in the main limited to flights traveling to other parts of Ireland and to Britain. Airlines based in Ireland include Aer Lingus (the former national airline of the Republic of Ireland), Ryanair, Aer Arann and CityJet.

Ireland has ports in major ports in Dublin, Belfast, Cork, Rosslare, Derry and Waterford. Smaller ports exist in Arklow, Ballina, Drogheda, Dundalk, Dún Laoghaire, Foynes, Galway, Larne, Limerick, New Ross, Sligo, Warrenpoint and Wicklow. Ports in the Republic handle 3.6 million travellers crossing the sea between Ireland and Britain each year.[92] The vast majority of heavy goods trade is done by sea. Ports in Northern Ireland handle 10 megatons (11 million short tons) of goods trade with Britain annually, while ports in the Republic of Ireland handle 7.6 Mt (8.4 million short tons).

Ferry connections between Great Britain and Ireland via the Irish Sea include routes from Swansea to Cork, Fishguard and Pembroke to Rosslare, Holyhead to Dún Laoghaire, Stranraer to Belfast and Cairnryan to Larne. There is also a connection between Liverpool and Belfast via the Isle of Man. The world’s largest car ferry, the MV Ulysses, is operated by Irish Ferries on the Dublin–Holyhead route. In addition, Rosslare and Cork run ferries to France.

Several (mainly hypothetical) plans to build an “Irish Sea tunnel” have been proposed. The first serious proposal was made in 1897, which was for a tunnel between Ireland and Scotland crossing the North Channel. Most recently, in 2004, the Institution of Engineers of Ireland proposed the “Tusker Tunnel” between the ports of Rosslare and Fishguard. In 1997 a British engineering firm, Symonds, proposed a rail tunnel from Dublin to Holyhead. Either of the two most recent proposals, at 80 km (50 mi), would be by far the longest tunnel in the world and would cost an estimated €20bn.

Irish railway routes with major towns/station, mountains, ports and airports. The railway network in Ireland was developed by various private companies during the 19th century, with some receiving government funding in the late 19th century. The network reached its greatest extent by 1920. A broad gauge of 1,600mm (5 ft 3in) was agreed as the standard the island, although there were also hundreds of kilometres of 914mm (3 ft) narrow gauge railways.

Long distance passenger trains in the Republic of Ireland are managed by Iarnród Éireann and connect most major towns and cities. In Northern Ireland, all rail services are provided by Northern Ireland Railways. Additionally, Ireland has one of the largest dedicated freight railways in Europe, operated by Bord na Móna totalling nearly 1,400 kilometres (870 mi).

In Dublin, two local rail networks provide transport in the city and its immediate vicinity. The Dublin Area Rapid Transit (DART) links the city centre with coastal suburbs. A new light rail system, the Luas, opened in 2004 and transports passengers to the central and western suburbs. Several more Luas lines are planned as well as an Dublin Metro. The DART is run by Iarnród Éireann and the Luas is run by Veolia under franchise from the Railway Procurement Agency. Under the Irish government’s Transport 21 plan, the Cork to Midleton rail link was reopened in 2009. The re-opening of the Navan-Clonsilla rail link and the Western Rail Corridor are amongst future projects as part of the same plan.

Services in Northern Ireland are sparse in comparison to the rest of Ireland or Britain. A large railway network was severely curtailed in the 1950s and 1960s. Current services includes suburban routes to Larne, Newry and Bangor, as well as services to Derry. There is also a branch from Coleraine to Portrush.

Motorists in Ireland drive on the left. There is an extensive road network and a developing motorway network fanning out from Dublin and Belfast in particular. Historically, land owners developed most roads and later Turnpike Trusts collected tolls so that as early as 1800 Ireland had a 16,100 kilometres (10,000 mi) road network. In recent years, the Irish Government launched a new transport plan that is the largest investment project ever in Ireland’s transport system: investing €34 billion from 2006 until 2015. Work on a number of road projects has already commenced and a number of objectives have been completed.

The first horsecar service in Ireland ran from Clonmel to Thurles and Limerick and was introduce in 1815 by Charles Bianconi. Today, the main bus companies are Bus Éireann in the Republic and Ulsterbus in Northern Ireland, both of which offer extensive passenger service in all parts of the island. Dublin Bus specifically serves the greater Dublin area and Metro operates services within the greater Belfast area.

Signposts and speed limits in the Republic of Ireland are shown in kilometres per hour, with speed limits having changed in 2005. Distance and speed limit signs in Northern Ireland use imperial units in common with the rest of United Kingdom.

Back to Top

Electrical & Energy Networks

For much of their existence electricity networks in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland were entirely separate. Both networks were designed and constructed independently post partition. However, as a result of changes over recent years they are now connected with three interlinks and also connected through Great Britain to mainland Europe. The situation in Northern Ireland is complicated by the issue of private companies not supplying Northern Ireland Electricity (NIE) with enough power. In the Republic of Ireland, the ESB has failed to modernise its power stations and the availability of power plants has recently averaged only 66%, one of the worst such rates in Western Europe. EirGrid is building a HVDC transmission line between Ireland and Britain with a capacity of 500 MW, about 10% of Ireland’s peak demand.

Similar to electricity, the natural gas distribution network is also now all-island, with a pipeline linking Gormanston, County Meath, and Ballyclare, County Antrim. Most of Ireland’s gas comes through interconnectors between Twynholm in Scotland and Ballylumford, County Antrim and Loughshinny, County Dublin. A decreasing supply is coming from the Kinsale gas field off the County Cork coast and the Corrib Gas Field off the coast of County Mayo has yet to come on-line. The County Mayo field is facing some localized opposition over a controversial decision to refine the gas onshore.

There have been recent efforts in Ireland to use renewable energy such as wind power. Large wind farms are being constructed in coastal counties such as Donegal, Mayo and Antrim. What will be the world’s largest offshore wind farm is currently being developed at the Arklow Bank Wind Park off the coast of County Wicklow. It is predicted that the Arklow wind farm will generate 10% of Ireland’s power needs when it is complete. The construction of wind farms has in some cases been delayed by opposition from local communities, some of whom consider the wind turbines to be unsightly. The Republic of Ireland is also hindered by an aging network that was not designed to handle the varying availability of power that comes from wind farms. The ESB’s Turlough Hill facility is the only power-storage facility in the state.

Back to Top

Demographics

People have lived in Ireland for at least 9,000 years, although little is known about the palaeolithic and neolithic inhabitants of the island. Genetic research in 2004 suggests they came to the island by traveling over generations along the Atlantic coast from Spain. Earlier theories were that they migrated from central Europe. Early historical and genealogical records note the existence of dozens of different peoples that may or may not be mythological, for example the Cruithne, Attacotti, Conmaicne, Eóganachta, Érainn, and Soghain, to name but a few. Over the past 1000 years or so, Vikings, Normans, Scots and English have all added to the indigenous population.

Ireland’s largest religious group is Christianity. The largest denomination is the Roman Catholicism representing over 73% for the island (and about 87% of the Republic of Ireland). Most of the rest of the population adhere to one of the various Protestant denominations (about 53% of Northern Ireland). The largest is the Anglican Church of Ireland. The Muslim community is growing in Ireland, mostly through increased immigration. The island has a small Jewish community. About 4% of the Republic’s population describe themselves as of no religion. About 14% of the Northern Ireland population described themselves as so.

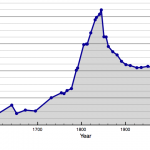

The population of Ireland rose rapidly since the 16th century until the mid-19th century. A devastating famine in the 1840s caused one million deaths and forced over one million more to emigrate in its immediate wake. Over the following century, a population heamorrhage reduced the population by over half, at a time when the general trend in European countries was for populations to rise by an average of three-fold.

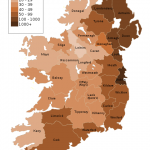

Emigration from Ireland over this period contributed to the populations of England, the United States, Canada and Australia where today a large Irish diaspora live. The pattern of immigration over this period particularly devastated the western and southern sea-boards. Prior to the Great Famine, the provinces of Connacht, Munster and Leinster were more or less evenly populated whereas Ulster was far less densely populated than the other three. Today, Ulster and Leinster, and in particular Dublin, have a far greater population density than Munster and Connacht.

With growing prosperity since the last decade of the 20th century, Ireland has become a place of immigration instead. Since joining the European Union expanded to included Poland in 2004, Polish people have made up the largest number immigrants (over 150,000) from Central Europe, followed by other immigrants from Lithuania, the Czech Republic and Latvia. The Republic of Ireland in particular has seen large-scale immigration. The 2006 census recorded that 420,000 foreign nationals, or about 10% of the population, lived in the Republic of Ireland. Chinese and Nigerians, along with people from other African countries, have accounted for a large proportion of the non-European Union migrants to Ireland. Up to 50,000 eastern European migrant workers may have left Ireland towards the end of since 2008.

English has been spoken in Ireland since the Middle Ages and, since a language shifts during the nineteenth century, has replaced Irish as the first language vast majority of the population. Less than 10% of the population of the Republic of Ireland today speak Irish regularly outside of the education system and 38% of those over 15 years are classified as “Irish speakers”. In Northern Ireland, English is the de facto official language but official recognition is afforded to both Irish and Ulster-Scots, which is also spoken by a number south of the border. In recent decades, with the increase in immigration, many more languages have been introduced, particularly deriving from Asia and Eastern Europe.